The location of la Hoya de Huesca, where the foothills of the Pyrenees meet de plains running down to the Ebro Valley, has made this area a melting pot of cultures and ways of life thoughout its history. After the Reconquest of the 11th century, formerly divided cultures became unified, while conservating the cultural differences which mark the natural and geographical setting of the towns.

We invite you to a journey in time…

ANCIENT HISTORY. There is evidence of human habitation in the territory of Hoya de Huesca from the Paleolithic period. These early settlers left many examples of their technological advances and changes in their beliefs and attitudes throughout Prehistory. Important archaeological findings have provided numerous examples of material culture. Some of the most prominent are on display at the Provincial Historical Museum of Huesca, where sequential didactic information about this human evolution has been provided through stone materials, bone and antler tools, metal parts and ceramic implements. In addition, visitors can see some singular manifestations of their funeral rites in the territory. Some 4,000 years ago (about 2,000 BC), megalithic monuments were erected in different parts of the mountains, such as the dolmen at Piatra in Belsué and the Palomar at Nocito.

Romanisation occurred in Hoya de Huesca in the 3rd century BC, and led to a significant boost in the building of towns, among other things. Thus, the Iberian Bolskan became the Roman Osca, which was a significant town in the region then known as Hispania Citerior. The city coined currency; was endowed with superb infrastructure (walls, temples, theatres, for example); villas flourished in their environment, such as Bajocuesta on the Apiés road; and much of this led to the building of mills and structures of pipelines and aqueducts to supply water to its inhabitants and their fields of crops; for example, the vestigial structure preserved at Quicena.

However, roads were one of the most distinctive and strategic constituents of the process of Romanisation. It was thanks to these that the legions were able to move swiftly, the territories were linked together and trade was boosted. Hoya de Huesca is entirely crossed with routes that travel from north to south and from east to west, with some sections being preserved, such as part of the Osca - Ilerda road in the town of Pertusa; which was a focal point in the Roman communication network in the north of the Ebro.

In the medieval period, the northern Sierras formed an important frontier between Christians and Arabs, the former confined to the mountains and the latter dominating the fertile southern plain. The natural defenses of these Sierras were used in the construction of castles and watchtowers in the period when the Kingdom of Aragon was extending its boundaries southwards and eastwards from the area of Jaca and San Juan de la Peña.

This military romanesque heritage has left fine examples in La Hoya, such as Marcuello castle in Linás de Marcuello, Loarre castle, Ordás castle in Nueno and the tower of Santa Eulalia la Mayor. Past the defensive line of the mountains, Montearagón castle, in Quicena, was decisive in the reconquest of Islamic Huesca. The city’s Arab defensive walls were breached in 1096 by the Aragonese King Pedro I; other fortresses of this period are the castles of Almudévar and of Novales, in the southern part of the Hoya, and the defensive walls of Antillón.

After the castles had fulfilled their military purposes, they were occupied by religious orders who would oversee the resettlement of the reconquered areas and their indoctrination in Christian dogma, while new monasteries were also built.

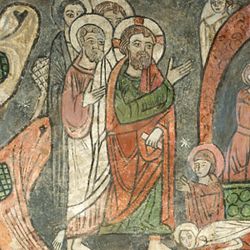

La Hoya de Huesca is rich in examples of religious Romanesque, such as those in Loarre castle, offering a contrast between the Lombard Romanesque of the first epoch and the later Romanesque in the style of Jaca. The castle-abbey of Montearagón was also home to a community of monks, and for a long period, stretching beyond the Middle Ages, it was a very rich abbey, controlling territories, assets and populations over a large area.

Other essential sites in this Romanesque heritage include the church of Santiago, in Agüero, an unfinished project which was to have been a branch of the Monastery of San Juan de la Peña; and the church of San Pedro el Viejo, in Huesca, which belonged to a Benedictine monastery built over an earlier Mozarab church. This has a lovely cloister leading onto the second and fi nal Pantheon of Kings of all Aragon; here lie the remains of Alfonso I El Batallador and Ramiro II El Monje, the perpetrator of the bloody massacre known as the Bell of Huesca and the founder of the Crown of Aragon, as he married his daughter to the Count of Barcelona, Ramón Berenguer IV.

Romanesque is by far the dominant artistic style in the Hoya de Huesca, which holds many more interesting examples in the parish churches of many villages, although these were largely altered in later periods.

The city of Huesca is also home to the most notable example of civil Romanesque in La Hoya: the Palace of the Kings of Aragon, now part of the Museum of Huesca –the Provincial Museum of Archaeology and Art– where we also find the lugubrious Sala de la Campana (Bell room), the scene of the legendary Medieval massacre.

Arab culture also left its mark on the Hoya de Huesca. As well as the defensive walls of the capital, dated to the 9th century, there are interesting ruins of Arab fortresses such as the remains of the castle of Los Muros, in Ayerbe, or of Tan Wa Man, on top of Salto de Roldán. In the southern part of the Hoya, the Arab castle of Piracés –also known as the Piedra del Mediodía or Midday Stone– is the best example of this type of fortress, which took advantage of the natural defenses provided by rocks and cliffs in strategic areas. In 1172 the Cistercian monastery of Nuestra Señora de Gloria was founded in Casbas de Huesca. This monastic centre has remained active, under its motto ora et labora, from its origins to the present day.

As time went by new towns and cities appeared, and with them new ways of life, a new concept of society and new styles of art and architecture.

In 1172 the Cistercian monastery of Nuestra Señora de Gloria was founded in Casbas de Huesca. This monastic centre has remained active, under its motto ora et labora, from its origins to the present day.

As time went by new towns and cities appeared, and with them new ways of life, a new concept of society and new styles of art and architecture.

This was the gothic period, with the best example being Huesca Cathedral. The present building was begun in the 13th century and for various reasons was not finished until the 16th. The bright interior is dominated by the outstanding Main Altarpiece, a Renaissance masterpiece carved in alabaster in the 16th century by Damián Forment. Many more works of art are scattered around the cathedral. To one side the former Chapterhouse and Cloister have been converted into the Diocese Museum, conserving many works of art of the diocese, with the Altarpiece of the Abbey of Montearagón being of particular interest.

Modern times… and up to nowadays.

The Renaissance saw an abundance of sculpture and painting in the form of altarpieces, and many of these can be enjoyed in the Museum of the Diocese of Huesca. The 16th century Collegiate Church of Bolea is the outstanding and most representative building of this period. Its bright interior is home to interesting works, especially the Main altarpiece, a spectacular combination of stonework and sculpture housing twenty tempera-painted panels, clearly influenced by Flemish and Italian Quattrocento art, created in the late 15th century by the Master of Bolea.

Renaissance building is dominated by civil buildings, casas de la ciudad –now Town Halls– and mansions. Some good examples of this Aragonese Renaissance style are the Ayuntamiento de Huesca (Town Hall), the former Town Hall of Loarre; the Palace of the Urriés, in Ayerbe; Villahermosa Palace, Casa Oña and Casa Claver, in Huesca; and many examples scattered around the Hoya de Huesca, all with brickwork façades, arched galleries on the top floor and pronounced eaves, combined in harmonious symmetry.

Other characteristic buildings of the late 16th century are the towers, freestanding or attached to churches, which are a focal point of many of our villages. Good examples are to be seen in Aguas, Loporzano, Angüés and Pertusa, this last in the Herrerian style, with a Romanesque crypt inside. Some of these towers were built in the Mudejar style, such as those of Alcalá de Gurrea, Montmesa and Nueno, the most Northerly example of this style.

In the Baroque period, the Basilica of San Lorenzo and the church of Santo Domingo y San Martín are the outstanding examples in the city of Huesca. The building of the Provincial Museum, in the same city, was originally the University of Huesca, and is a landmark in the civil building of the era.

In the 19th and 20th centuries various architectural styles were developed; Historicism, the imitation of earlier periods in new buildings, is especially visible in Huesca: Santa Ana School, the Hacienda Tax Offices, the Post Office building and Olimpia theatre. Huesca also has its Casino (1901), the best example of Art Nouveau of this territory, as well as good examples of civil architecture in Rationalist and Contemporary styles. Contemporary art in the form of sculpture is nurtured by the programme Arte y Naturaleza (Art and Nature), managed in the province by CDAN, the Huesca Centre for Art and Nature. Two interesting examples can be seen in natural settings in the Hoya: the hill of Piracés and the poplar woods of Belsué. Eternal nature, as a backdrop for contemporary art.

Once again, the Hoya de Huesca is fusion and diversity.

military tourism

The Spanish Civil War battlefront left its imprint on the Hoya de Huesca countryside for a long period of time, leading to the establishment of a vast and diverse catalogue of infrastructure and military equipment. Both sides dug trenches and underground shelters, built bunkers, pillboxes, ammunition dumps and bomb shelters.

Some of the most complete Republican trench systems have been preserved and marked in Siétamo and Tierz, where illustrious European intellectuals joined and fought for the International Brigades, such as George Orwell, Willy Brandt and John Cornford. While at Puilatos (Gurrea de Gállego), a network of trenches and bunkers designed by the Franco side still remains.

Another highlight in Hoya de Huesca is the town of Vicién, which served as the command centre for the anarchist forces in the area. Here, a number of sites can be visited, such as the preserved and painted requisitioned houses, air-raid shelters, magazine stores and a cave carved into the rock and used as a control room, as well as an imposing ice well which was modified and used for military purposes.

popular culture

La Hoya de Huesca has many interesting examples of cultural heritage and ancient symbolism directly linked to nature, displaying the intimate relationship of people and their environment. For example, the many ice houses, used to store winter ice and snow which would later be used in summer; good examples in the Hoya can be found in Vicién, Almudévar, Salillas, Casbas de Huesca and Nueno.

The search for underground springs began in the medieval period and under Arab influence, with the best examples of wellsprings being those of Albero Alto, Piracés, Antillón, Blecua, Ola, Velillas and Angüés.

Underground cellars, excavated in the hills of towns and villages, are a third group of elements of our popular culture, of ancient origin. They are especially numerous in the villages of Almudévar, Alcalá de Gurrea, Puibolea, Bespén, Blecua and Antillón. Most are still used by local households. The Vineyard, Wineries and Wine Interpretation Centre of Almudévar explains this type of popular cultural heritage.

Combining cultural heritage and pagan symbolism, and linked to fertility rites of ancient origin, is the Fertility Stones route, rock formations altered by human hands to enhance their appearance of human reproductive organs, and thus becoming sacred temples of fertility where women and men could go to cure problems of this type. This route is in the south-eastern part of La Hoya, in the villages of Piracés, Ayera, Fañanás, Ibieca, Sesa, Tramaced and Velillas.